Finding Out About Files

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I use Python and pymediainfo to learn more about media files?

Objectives

“Use for loops on lists of objects”

“Use os.stat to get file size”

“Install packages with pip”

“Use pymediainfo to collect duration”

Asking questions about a list of files

Alice jumped in with both feet and knocked out a lot of transcoding work. However, she had some lingering questions about how effective all that transcoding was and if different codecs had different results. To understand that, she needs to collect metadata about her files.

Look Before You Leap vs. Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission

Generally, Alice and anyone else working with collections would do this before copying, moving, or transcoding any files. This is also an approach to Python programming called Look Before You Leap. In other words, before you perform an action make sure you understand the consequences of that action.

For this workshop, we want participants to experience some big results early on. So those lessons were done in the spirit of another approach to Python programming called It’s Easier to Ask For Forgiveness than Permission. In this approach, you perform actions with the expectation that nothing terrible will happen as a result. For us, we left all of the original files alone. If there had been an error in our code or the results, it didn’t affect the original collection, so all we would have lost was our time.

While learning how to create filepaths and transcode files, we created our first few building blocks:

- import modules

- generating lists

- building

forloops

Within an AV preservation environment, we will use these building blocks repeatedly for two common tasks:

- information gathering (analysis)

- processing (manipulation)

Frequently, these two tasks go hand in hand. We may generate monthly/quarterly/annual reports about the size of the collection for administration, and then use this information to perform actions like estimating storage needed for service copies or deciding to losslessly transcode everything.

Metadata about Media Files

If we want to compare the technical characteristics of the Quicktime files and MKV files, what are some of the key pieces of information that we’ll want collect?

Solution

TOTAL NUMBER OF FILES! SIZE! DURATION!

As usual, we will have multiple ways to retrieve this information. Let’s begin by reviewing a few ways Python can be used to determine some of the overarching characteristics of our media collection

- How many files do we have?

- How big are they individually and cumulatively

- What is the duration of each file/our set of files?

Just to make sure we’re setup right, here is the code for creating our digital shelflist.

On Mac:

video_dir = '/Users/username/Desktop/pyforav'

On Windows:

video_dir = 'C:\\Users\\username\\Desktop\\pyforav'

mov_list = glob.glob(os.path.join(video_dir, "**", "*mov"), recursive=True)

Finding the total size of all AV files in a directory

os.stat

A good place to start is with os.stat, a piece of the os module that provides information on the “status” of a file.

The stat module offers a wealth of detail related to ownership, permissions, location, creation/modification times, but for our purposes, we’ll be using it to determine file sizes.

Our end goal is to write a for loop that collects the size of each file.

As we did in previous lessons, a good strategy to build towards the for loop is to apply the code to a single element of our list.

Let’s see how os.stat works on the first path in mov_list.

First, we have to import the os module.

import os

os.stat(mov_list[0]).st_size

The result is a number. It’s important to notice that it doesn’t have quote marks around it like a string.

Python Syntax: Integers

In Python, integers consist of numbers

0through9and nothing else. No decimal points. No quotation marks. You can do math with an integer:2 + 2 = 4If you do the same math with strings, you will get a very different result:

'2' + '2' = '22'

Numbers that don’t act like numbers

What are examples of numbers that you use that you wouldn’t want to do math with?

Solution

Barcodes often consist of numbers, but it wouldn’t make sense to add 2 barcodes together, or compare them to see if one is larger than the other. It can be much easer to store barcodes as strings, despite how much they look like integers.

We can adapt this code into a for loop to look at all of the files.

for item in mov_list:

print(os.stat(item).st_size)

This list would be more useful if we know which number is associated with which file. One way to do this is by using string formatting.

for item in mov_list:

print('File: {}, Size: {}'.format(item, os.stat(item).st_size))

But even better than descriptive print statements is gaining an aggregate sense of the data we have on-hand. To accomplish that, we will save the sizes to a list, instead of immediately printing them out.

size_list = []

for item in mov_list:

size_list.append(os.stat(item).st_size)

Now, with our file size list, we can add our numbers together with the sum function.

sum(size_list)

While os.stat provides us with the size (number of bytes as integers) of our files, it can be very hard to tell if you’re working with 10’s of terabytes (10000000000000) or 100’s of gigabytes (100000000000).

When humans write numbers, we often use commas to help with this problem, but computers don’t need or want the help of commas. If we want to express the total number of bytes as terabytes, we need to ask for that ourselves.

For example:

totalsize = 16255932760371

totalsize/(1000 ** 4)

16.255932760371

Here, ** is the Python notation for an exponent, so 1000 ** 4 means 1,000,000,000,000 and 16.255932760371 is the number of terabytes

TB vs. TiB

If you’re wondering why we’re using 1000 instead of 1024 for our math, you’re asking good question.

And the answer points to a long, and honestly, quite frustrating history, but it is worth taking a quick tangent.

The tl; dr is: computer scientists really love binary systems and think 2 ** 10 or 1024 is a convenient large group.

Engineers really love base-10 systems and think 10 ** 3 or 1000 is a really useful group.

For a while, both of these communities used the same prefixes for their numbers.

A computer scientist would talk about a kilobyte with 1,024 bytes and an engineer would talk about a kilobyte with 1,000 bytes.

In the 90s, they “settled” their dispute. To talk about base-10 numbers, you should use the familiar SI (International System of Units) prefixes: kilo- (k), mega- (M), giga- (G), tera- (T), etc.) To talk about binary numbers, you should use the binary prefixes: kibi- (ki), mebi- (Mi), gibi- (Gi), tebi- (Ti), etc. Unfortunately, they didn’t really settle the debate, and you can still find marketing materials that mix the two up. For us, it’s an important distinction as our collections grow bigger. Take the 16 trillion bytes from the example above.

totalsize/(1000 ** 4)

16.255932760371

totalsize/(1024 ** 4)

14.784684717934397

16.2 TB seemingly shrank down to 14.7 TiB. It didn’t really shrink, but the units that we used to measure can change our perception. If this is all feeling a little rabbit-holey and inane, just know: how you communicate about data does matter, especially given this long-standing historical confusion. If your storage provider sells storage by the TB while you calculate by the TiB, you might be surprised by your bill. Clarity is Queen!

Collecting duration information

Let’s turn from bytes to duration, another key piece of information that we’ll often be asked to aggregate when we begin to work at scale (average duration by format can help when forecasting anticipated needs).

Here, we’ll call upon another Python package: pymediainfo, a Python wrapper for the open source technical metadata tool MediaInfo.

pymediainfo is the shit, and though there are other ways to incorporate MediaInfo into our Python code, pymediainfo is elegant and has a relatively low bar to entry.

We’ll touch upon many of the different ways that Python + MediaInfo can assist with AV file management, but let’s start with installation and the process of gathering up the durations of our files.

Installing packages with pip

This is the realm of package management, and if any macOS users are familiar with Homebrew, the program pip plays a similar role within Python, allowing users to install “packages,” or specialized code libraries designed to perform specific, not-handled-by-default tasks.

So we’re back to importing modules, as it were, though these outside modules first require a separate installation step (via pipenv) before we can import and use them in our code.

As we’ve all installed Python3 via Anaconda, we’ll have pip available to us.

But, to check our installation, we can do the following.

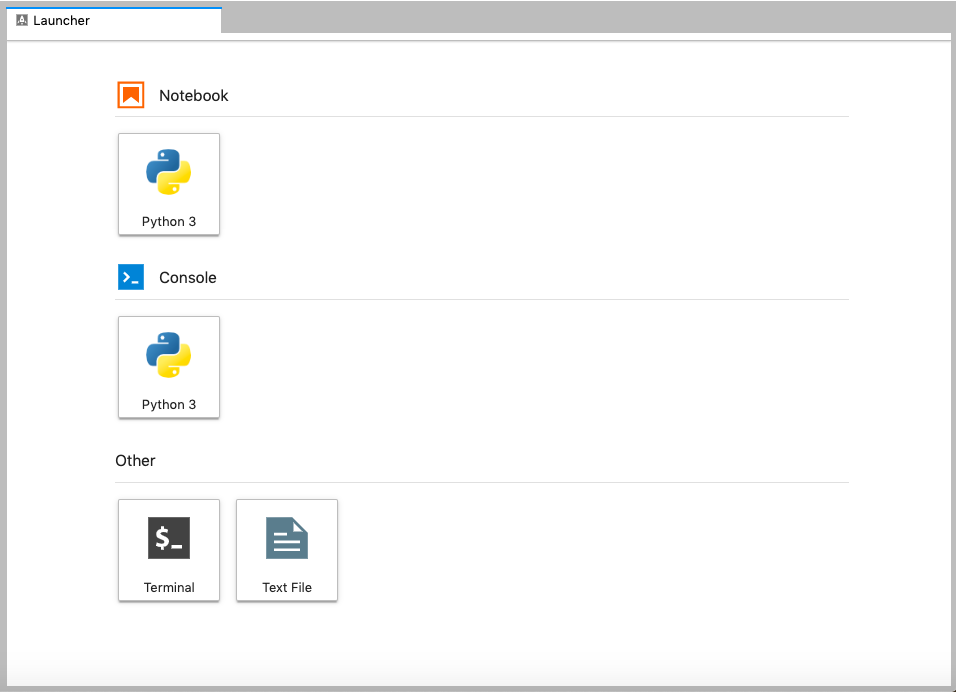

First, open a console Terminal tab in Jupyter by clicking on the + sign in the sidebar and clicking on the Terminal tiles in the main area.

When the terminal opens, it should look like the following.

username@computername >

pipenv offers a lot of features, but the one most relevant to us is related to this process or installing/uninstalling, and listing packages located in what’s called the Python Package Index, or PyPI (remember too that pip -h will direct you to handy help pages).

And to install pymediainfo, we do the following:

pipenv install pymediainfo

To check that we’ve installed pymediainfo properly, we can list all of the packages that we’ve installed via pip:

Already installed

Your

pipenv installcommand may report that pymediainfo has already been installed. We weren’t sure how well the Internet would work during this workshop, so we pre-installed it during the setup.

Using pymediainfo

This time, when we import the module, we’ll get a bit more specific.

from pymediainfo import MediaInfo

Python Syntax:

fromand importsSo far we’ve always imported the entire module, but sometimes you only need a portion of the module. That can be because the module is large, you don’t want to waste time loading unnecessary components. Or it can be because the part you need is buried deep in the module, and you don’t want to write

module.submodule.functioneverytime.For this we can use the

from module import submodulestatement. This loads only the specific submodule named. It is loaded assubmodule, so we don’t have to writemodule.submoduleeverytime.

To use pymediainfo we’ll need to understand how pymediainfo creates a special class for MediaInfo track-related information.

We’ve already worked with a special class when we used the 'string'.replace() method.

pymediainfo produces nested data objects with similar notation.

To see this in action, first we look at the data it generates from one file.

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(mov_list[0])

for track in media_info.tracks:

print(track.track_type, track.duration)

General 468

Video 468

Audio 465

If we break this down into discrete units, we’ve got three key steps:

- running and parsing the output of MediaInfo on a single file, then storing that technical metadata to a variable for us to retrieve;

- looping through the

tracksthat MediaInfo reported on - printing out, in our Jupyter notebook, the name of each track and its duration.

We can tweak this in any number of ways. First, we can limit our printing to only the ‘General’ track.

if conditionals

When we only want code to run under certain conditions, we use logic tests.

The most common of these is the if statement.

An if statement can be read like this: If this is true, then do the following. If this isn’t true then do something else.

Python Syntax:

ifstatementsIn the case of Python, there are a few important things to keep in mind about

ifstatements. The first line of a for loop always looks similar to this:if logic_test:

- if - tells Python it will be testing if the following statement is true or not

- logic_test - any code which resolves to true or false The logic_test portion is commonly a test like, “Is this variable equal to a value?” (

string_variable == 'string') or “Is this number greater or less than another?” (number_variable > 55).

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == 'General':

print(track.duration)

Working with Time

By default, pymediainfo returns the time in milliseconds. This is frustrating, in that we generally don’t talk about a time in milliseconds.

We could, for example, have our print statement be more human-readable by using Python’s print formatting function.

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == 'General':

print("Duration: {} sec.".format(track.duration / 1000.0))

So here, we ask Python to do two additional things: (1) format the print statement to read, “Duration: X sec.”; and (2) divide the milliseconds value by 1000, to return seconds.

Finally, we can use a for loop to get this information for every file.

for item in mov_list:

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(item)

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

print("Duration: {} sec.".format(track.duration / 1000.0))

Duration: 0.468 sec.

Duration: 0.111 sec.

Duration: 0.267 sec.

Duration: 0.568 sec.

Duration: 1.085 sec.

Duration: 0.337 sec.

Duration: 0.935 sec.

...

As an alternative, we could take advantage of MediaInfo’s already verbose output, and if we recall, when we ask MediaInfo for a “full” report (mediainfo -F my_movie.mov), we receive a few different expressions of the same value:

pymediainfo allows us to access these various options:

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(mov_list[0])

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

print(track.to_data()["other_duration"])

['317 ms', '317 ms', '317 ms', '00:00:00.317', '00:00:00;09', '00:00:00.317 (00:00:00;09)']

If we wanted to select a single choice from this list output, we could subscript in the following way (while keeping in mind that Python is always zero-indexed):

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

print(track.to_data()["other_duration"][3])

00:00:00.317

This is an even more human-readable option, but when we try to sum up the entire collection, that human-readability can be a liability.

durations = []

for item in mov_list:

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(item)

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

durations.append(track.to_data()["other_duration"][3])

sum(durations)

Python Syntax: Function Errors

The sum function is designed to work with numbers, so if our list contains strings, Python will print out an error message.

sum([2, 2, '2'])TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'Some functions have strong requirements for what kind of data can be used as an argument. When you see an error like this, read it and see if it makes sense. Most errors messages will start with the most general information and get more specific.

TypeError- the function can’t work with the type of data providedunsupported operand type(s) for +- the function specifically can’t use+for the data provided'int' and 'str'-+cannot be used for a mixture of integers and stringsProgrammers don’t always write understandable error message, but copying-and-pasting your error message to a search engine can often help you find people asking the same questions and getting better explanations.

Python Syntax: Finding help for Python functions

If you run into an error, Python offers built-in help pages that can yield insight into the inner-workings of different modules, classes, functions, etc. Google/Stack Exchange are always a good place for additional information, but sometimes it’s most handy to get the lowdown directly from the source itself.

So let’s use the sum function, and walk through how to pull up Python’s help pages. Type the word ‘help’ and follow it with the item about which you’d like more information, contained within parentheses:

help(sum)Help on built-in function sum in module builtins: sum(iterable, start=0, /) Return the sum of a 'start' value (default: 0) plus an iterable of numbers When the iterable is empty, return the start value. This function is intended specifically for use with numeric values and may reject non-numeric types.To exit the help pages, type the following:

quit()

While calculating is easier with milliseconds (integers), reading is far easier to do in HH:MM:SS:MS (strings). Our challenge is to do all of the calculating with milliseconds and then print the final result as HH:MM:SS:MS. Now, this being the wide world of Python, there is a module (called datetime) that we could use to transform our HH:MM:SS:MS into a shape (called a datetime object) that could be manipulated, but for now, let’s stick to a more manageable solution.

As with our summing of bytes, we can make a few small changes to our code to add our individual durations to a new list:

durations = []

for item in mov_list:

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(item)

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

durations.append(track.duration)

sum(durations)

69327

To create something more human readable, we could perform a series of equations to transform this value into HH:MM:SS:MS, or we could use some prebuilt Python modules. Both are demonstrated below.

total_duration = sum(durations)

hours = total_duration // 3600000

minutes = (total_duration % 3600000) // 60000

seconds = (total_duration % 60000) // 1000

ms = total_duration % 1000

human_duration = "{:0>2}:{:0>2}:{:0>2}.{:0>3}".format(hours, minutes, seconds, ms)

human_duration

'00:01:09.327'

import datetime

total_duration = sum(durations)

human_duration = datetime.timedelta(milliseconds=total_duration)

human_duration

'00:01:09.327'

With all of the complexity and unfamiliar syntax of the first example, we think the second approach is preferable. The challenge in finding that approach is knowing where to ask for help. Your colleagues are always a good first stop. Even if they don’t know the answer, they can help you refine your question.

Challenge

How would you find the average duration of the files?

Solution

sum(durations)/len(durations)

Putting it all together

We can put all of the pieces together, using pymediainfo, a slew of for loops, multiple lists, glob, datetime, and a formatted print statement to result in a script that will comb through our directory, count up all of the relevant media files, and let us know: (1) the total number of files, (2) the average duration in human readable form, and (3) the average file size, in the SI system.

mov_list = [ ]

sizes = []

durations = []

mov_list = glob.glob(os.path.join(video_dir, "**", "*mov"), recursive=True)

for item in mov_list:

media_info = MediaInfo.parse(item)

for track in media_info.tracks:

if track.track_type == "General":

durations.append(track.duration)

sizes.append(track.file_size)

avg_duration = int(sum(durations)/len(mov_list))

human_duration = datetime.timedelta(milliseconds=total_duration)

print("Total Number of Files: {} ; Average Duration: {}; Average Size: {}".format(len(mov_list), human_duration, sum(sizes)/len(mov_list)/1e6))

Total Number of Files: 135 ; Average Duration: 00:00:00.513; Average Size: 9M

Key Points

Start with the shortest piece of code and build up your pieces gradually